|

|

Home

|

|

|

Numeracy Framework

|

|

Rhythm of

Life -- Maths for Very Special Pupils Albert Einstein said: "Since the mathematicians have invaded the theory of relativity, I do not understand it myself any more." |

|

|

Summary Teachers working with pupils with severe or profound learning difficulties have a very positive track record of curriculum development. From the birth of the National Curriculum they were determined to ensure their pupils had access. Drawing on their knowledge of language development they have produced well-documented materials and their work has enabled their pupils to access to the English curriculum appropriately, to develop their skills and appreciation of communication. This work has facilitated suitable approaches to implementation of the literacy hour for very special pupils. Following the introduction of the Numeracy hour schools for very special pupils have taken the National Numeracy Strategy framework and adapted it to meet the needs of very special pupils. This article discusses the nature of fundamental mathematics and its importance to pupils with severe or profound learning difficulties, and suggests appropriate approaches to enhancing the National curriculum to meet their needs. These processes are entirely in accord with the QCA "Guidelines for planning, teaching and assessing the curriculum for Pupils with learning difficulties", as published in 2001. |

| Should we suffer maths anxiety? |

|

|

For many people mathematics has an aura of mystery about

it, and there is a tendency to think of it in terms of an academic subject

that involves abstract thinking and complex calculations. Looked at in

such light its relevance to pupils at early stages of development seems

marginal. In practical reality we use mathematics throughout our every

day lives. Mathematics is about space and quantity, we use it to understand

and influence the world around us. Its basic concepts are so natural to

us they are part of the thinking we do even before we speak. The part that mathematical thinking plays in our subconscious reasoning is very important to our conscious functions and appreciation of life. Whilst we enjoy conversation, and hearing about our world reflected through the wonder of language, in stories poetry and song, and recognise that these are part of the "English" curriculum. We also understand and enjoy our world through appreciation of space, shape and form, patterns and rhythms, but we are less inclined to recognise that these are "Mathematics". |

|

Learning through a feeling for space and time. It is interesting to note that Einstein, one of the greatest mathematical minds, described his creative mathematical thinking as, He said that words and other signs that could be used to try to describe his feelings only came into use after the initial "associative play." What better witness could we have to testify that mathematical understanding has physical and sensory origins, even wider and more basic to our life functions than knowledge of "numeracy". |

| Understanding starts early |

|

|

In articles in Special Children Carol Aubery described

the rich background of mathematical knowledge children develop by the

time they start school. Children as young as two develop intuitive sense of addition and subtraction. Before they start school many children have begun to construct their mathematical thinking, and have their own personal strategies for counting, practical addition etc. They are able to use this knowledge in specific practical situations, which they are familiar with, but are not always able to generalise their knowledge to other settings. For example they may recognise number 13 if it is the number of their house, but not relate the number to a quantity. (Vygotsky 1978). So even before formal teaching very young children are actively learning the basis of mathematics from experience. They are building up a fund of knowledge, when they go to school the teacher’s job is to build on the fund, to help them to link their personal knowledge to abstracted ideas and the formalised systems which everyone else uses. Special children who are developmentally different may have barriers to learning, and not be able to use their senses and social interactions to build up this fund. When they arrive at school they may not be ready to embark upon learning the numerical and computational aspects of mathematics upon which the framework of the Numeracy hour is likely to focus. Nevertheless mathematics is important and useful to them in many ways. |

| Living mathematics |

|

|

Mathematics is an essential part of communication Communication requires that we are able to comprehend and express the nature and order of things. English and maths use similar processes and complement each other in practical communication. For example "Joint action" and "turn taking" have patterns which facilitate prediction. Whilst understanding "object permanence", is needed to comprehend quantities and changes. Bringing items together, separating, sharing etc are all experiences that relate to quantities or events. Set in real life contexts they are situations that motivate discussion, create curiosity, stimulate predictions, or consideration of probability, they may promote agreement or disagreement. – In such situations communication is promoted alongside the development of mathematical concepts. Maths is a powerful tool for practical activity, and for learning more Mathematical concepts are basic to skills required for many practical purposes. For example how could we lead our everyday lives without understanding "one to one" relations, or appreciating increase and decrease? Skills of counting and arithmetic may develop from such concepts but even those skills are not ends in themselves, they are essential tools not only for daily living but also further learning. Maths helps us appreciate relationships The language of mathematics describes space, quantities and events, with it we can compare things and describe changes. Moreover the various parts of maths are themselves interrelated and its language describes relations. For example sorting is related to discrimination; volume to size; subtraction to addition; algebraic pattern to multiplication. In practice no one idea stands alone and learning one set of ideas will also help us understand related concepts. For example observing a pattern of multiplication will also help us understand division. Maths helps us be systematic Using its structures and language we can record and bring order to our observations. We can put experiences into memorable form. Looking for and describing patterns we can move forward from trial and error, and improve our powers of estimation and prediction. Developing systematic approaches helps make learning clear, and we can remember things better the next time we encounter a similar situation. This applies as much to concepts of quantity,order or space and time, as it does to remembering number bonds and tables. Mathematics is a tool of the imagination The structures of mathematics use systematic rules but they are not necessarily restrictive, rules can help put imaginative responses into order. Learning benefits from a two-way relationship between systematic thinking and imagination. When mathematical concepts are brought to bear on an experience new knowledge may dawn. This may be through gradual development or sudden revelation. It is true for children or for great thinkers. Archimedes struggled with how to measure the volume of an irregular object until he got in the bath. Newton was hit on the head by inspiration. Maths is fascinating Even though many people are anxious about mathematical language and processes they are often fascinated by patterns, changes and comparisons, they are also interested in outcomes and predicting them. These fascinations are powerful tools to motivate communication and learning. |

Mathematics is

|

| Mathematics is in the course of life |

|

|

Mathematics is so beguiling that it even creeps into our

enjoyment. Mathematical patterns and emotion are connected. Play rock

and roll, or play a waltz, and the counted rhythms are quite different,

but each of the patterns have undeniable charm in their power to move

us. Across the catalogue of music there is an amazing range of variations

on this theme, and the connections between music, movement, emotion, and

thinking suggest that those patterns have important influences on our

physical and mental development. Professor Ian Stewart described the connections

between, mathematics, bodily rhythms and movement in the Royal Institute

Christmas Lecture in 1997. He also related geometry to our responses to

visual arts. The influence of pattern is wider than music, speak in nursery rhyme or through a Shakespearean stanza and the magic of pattern will be there. Even changes of intonation in music or voice have mathematical dimensions, and these are important in even the earliest of children's communications. As Ian Stewart emphasised, "The mathematical mind is rooted in the human visual tactile and motor systems. Counting is based on touch and movement, geometry is visual". Let my hand trace a sphere, or grasp a banana I will sense differences, my sense of enquiry will be roused in contrasting ways, I will want to tell you different things. We are constantly exposed to experiences, both of practical necessity and of pleasure which have mathematical aspects, and which stimulate our natural desires to communicate and know more. Such experiences provide opportunities to expand children’s knowledge, and these areas of connection where mathematics and early cognitive development are intertwined are important for children who are at early stages of development. However the Programmes of Study for Mathematics in the National Curriculum assume that before they start school children have developed many skills that support mathematical understanding, and therefore they skim over the relevance of underlying experiences upon which mathematics is built. They assume that before children start school they have already developed the basic intuitive understandings, which are the basis of mathematical thinking. Consequently the Programmes of Study make little reference to early cognitive activities that are the basis of everyone’s mathematical knowledge. In these respects they are not detailed enough to help us recognise or organise mathematical learning for pupils with very special needs and they need to be enhanced. Similarly the framework of the National Numeracy Strategy needs to be adapted to relate to patterns of learning suitable for such students. |

| Enhancing the curriculum |

|

|

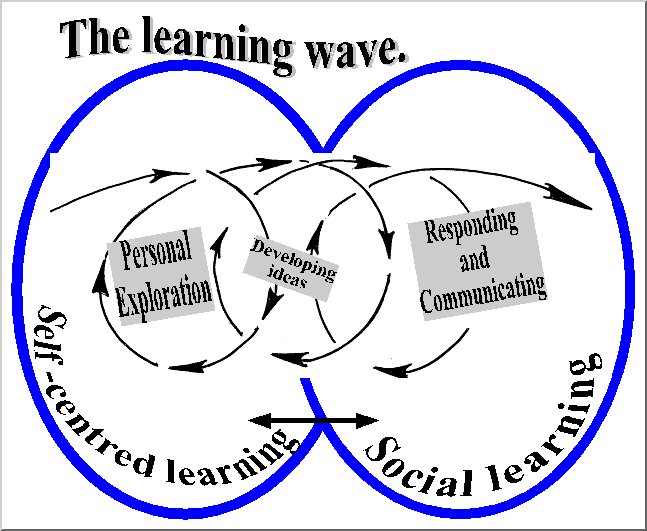

Taking account of patterns of learning Learning is driven by curiosity it begins as children explore with their senses. They realise significant things about their observations and develop ideas through which they begin to understand about things and relationships. They respond, communicating both about the ideas they have developed and the questions that their ideas and curiosity raise. The processes of these stages spiral forward like waves. There is repeated feedback and progression, as personal exploration results in gaining knowledge, and developing ideas, which encourage responses and so promote communication. Learning thus progresses from self-centred exploration towards social communication, and with feedback progresses again in a smooth flow. |

| Personal and Social Maths Lead Towards Numeracy |

|

The processes I have described make up the earliest stages

of our pupils’ mathematics.

|

Personal and social mathematics lead towards numeracy

|

| Processes of interactive teaching and learning |

|

|

This sequence of learning points us towards using processes

of interactive teaching and learning as means of offering our special

pupils access to the National Curriculum. Through interactive teaching

bulding upon sensory exploration, developing perceptual and attention

skills we can encourage biological, cognitive and social experiences that

promote bedrock mathematical understanding. Our approach should take advantage of cross-curricular opportunities, but mathematical detail does need to be described if it is to adequately guide our teaching, and provide for recording learning. As we delve more deeply into what is "Personal and Social Maths" it will be evident that much of what will be described is already present in good practice working with very special pupils. However it is important to outline detail of activities and processes because we need to understand how the jig-saw pieces of our teaching fit together. A wealth of "Personal maths" occurs in sensory sessions, and "Social maths" occurs whilst communication is being promoted. Knowledge of detail will equip us to exploit and emphasise the mathematical aspects of those experiences. It will also make us aware of pupils’ progress and more able to credit their achievements. |

| The next article entitled "Magnifying

Maths" will relate theory to practice and offer some content

for the structure described in this article. It will consider:- Personal and Social Maths For Very Special Pupils The development of mathematical ideas:-

Beginning Numeracy For Special Pupils

|

| Bibliography |

|

|

|

Les Staves Retired as the head teacher of Turnshaws Special School in Kirklees following an outstanding Ofsted report. He has thirty years teaching experience in mainstream and special education. He now works as a freelance trainer and consultant. |

|

|

|